Today we are pleased to welcome guest blogger, Diane Nelson Bryen, to share her perspective on expanding communication for individuals using AAC beyond face-to-face interactions.

—–

Introduction

Do you remember when people with complex communication needs could not communicate via telephone? Well as they say, “you’ve come a long way, baby.” However, we’ve neither come far enough nor fast enough. Are we still being left behind?

The purpose of this SpeakUP blog is to share the history of telephone communication and our slow move towards “accessing the world any time and from anywhere.” Your experiences and ideas about how to better access the world anytime and from anywhere are welcomed.

Landline Phones—Not for All!

It was not so long ago that many children and adults with complex communication needs learned to use communication boards. They could finally communicate face-to-face with familiar and, to some extent, unfamiliar people. However, without understandable speech, there was little or no access to communication via landline phones that use metal wire or optical fiber for voice transmission. In most cases, we were limited to communicating exclusively in face-to-face situations while our peers without disabilities could communicate with others from almost anywhere.

Landline Telephone © Ozgur Coskun – stock.adobe.com

Speakerphones

In the late 1980s, two advancements in communication technologies occurred, reducing the communication limitations experienced by people with complex communication needs. Voice output communication devices, now referred to as speech generating devices (SGDs), became available to many children and adults with complex communication needs. Simultaneously, mainstream landline speakerphones were developed for the general population. The microphone and loudspeaker incorporated into the design allowed hands-free communication by one individual or a group of people. This advance was welcomed by the general population.

Speakerphone for

Conversing with Multiple Persons © Cyril Lutsenko – stock.adobe.com

Speakerphone © Scanrail – stock.adobe.com

Adults with complex communication needs also celebrated the availability of landline speakerphones. Speakerphones enabled more independent and more private communication via telephone for individuals using SGDs. Of course, they still needed to dial the desired number using either hands or special SGD capabilities. Conference calls with multiple people in different locations was now possible. Larger buttons and braille buttons for dialing made access to speakerphones easier for individuals with visual or physical disabilities. Better volume control broadened the use of speakerphones for those with hearing disabilities. By 1995, 75% of individuals with complex communication needs reported that they communicated using a speakerphone (Bryen, Sleseransky, & Baker, 1995). One person commented that “knowing that if we ever need someone to talk to, the wires that line the sky will carry our needs.”

Mobile Phones

Shortly thereafter, mobile phones were developed for the general population so that they could make phone calls or send text messages to anyone from wherever and when ever as long as cellular towers existed at both ends. Use of mobile or cell phones grew dramatically. By the turn of the 21st century, mobile phones had reached a majority of the populations in Canada, the United States, Australia, Germany, Singapore, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Italy.

Mobile Phone © Cyril Lutsenko – stock.adobe.com

However, these small mobile phones were not easily accessible by many with complex communication needs despite the fact that SGDs were becoming more and more intelligible. A large digital divide existed between people with and without disabilities in their use of mobile phones. Gaps in usage occurred across all age groups. One study reported that only 20% of adults with complex communication needs used mobile phones (Bryen, Potts, & Carey, 2006). For more than a decade, however, the need for accessible mobile phones had been expressed as a means of improving health and safety; managing transportation; communicating with employers, friends, and families; and communicating in times of emergency (Bryen & Pecunas, 2004). The reasons for this gap were many, including cost of the mobile phone and its cellular service. The lack of accessibility was due to small buttons, the requirement to hold the phone in one’s hand, and the lack of interconnectivity with SGDs.

In attempts to address some of the deficits of these new mobile phones, people using SGDs began to devise off-the-shelf solutions such as adapting hands-free mounts intended for use while driving cars for use on wheelchairs (Bryen & Pecunas, 2004). With some modification, mobile phone batteries could be charged using the batteries of powered wheelchairs. The standard microphone from the cell phone needed to be positioned on the wheelchair so the speech of the person or the synthesized speech of the communication devise could be transmitted. However, adapting a mainstream mobile phone using off-the-shelf solutions placed an unnecessary burden on many individuals with complex communication needs.

The gap in the use of mobile phones by people with complex communication needs and their peers without disabilities did, however, decrease. According to Bryen and Moolman (2015), the reduction in this digital divide was due, in part, to the following:

- “Applying principles of Universal Design in the development of new mainstream mobile technologies,

- Improving interconnectivity between speech generating devices and mainstream mobile phone technologies, and

- Recognizing that access to mobile phone technology is a human and civil rights issue” (page 1487).

Smartphones

With the further development of cellular technology used in mobile phones, Smartphones began to replace single-function mobile phones. Smartphones, which debuted in 1995, enabled the person to do more than just communicate with others from anywhere and at any time. This technology essentially put computers in people’s pockets, providing a touchscreen interface, internet access, and an operating system capable of running downloaded applications. With these multifunction phones, individuals with a disability could potentially log in and order groceries, shop for appliances, research health questions, participate in online discussions, navigate cities, travel more independently, and catch up with friends or make new ones at any time and anywhere (Center for an Accessible Society, n.d.). Despite the benefits of this new technology, the Center on Wireless Technology found that adults who use AAC devices used these smartphones at substantially lower rates than their peers from other disability groups, such as those who have visual or hearing disabilities. The main reason for this gap was due to the continued lack of accessibility of smartphones for those with complex communication needs (Morris & Bryen, 2015; Wireless RERC, 2014).

Smartphones © Scanrail – stock.adobe.com

The Promise of Intelligent Digital Assistants

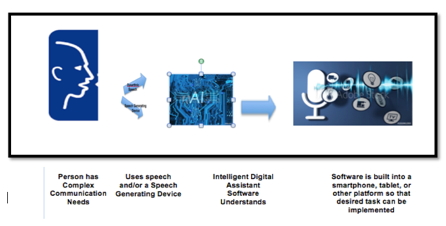

In order to better understand how these accessibility barriers might be reduced, a focus group of adults with complex communication needs who use both SGDs and mainstream mobile phones was established (Bryen & Chung, 2017). Among their suggestions was the possible use of intelligent digital assistants. An intelligent digital assistant is a software service coupled with a computing device that answers questions and performs tasks using voice and natural language processing (Krupansky, 2017). None of the focus group participants were currently using this powerful technology. One participant shared that if intelligent digital assistants could understand our voices–natural or synthesized, it would be “A GAME CHANGER!”

Today, intelligent digital assistant software is being used by millions of people worldwide. It has been built into smartphones that can be used anytime and anywhere as long as there is access to either WIFI or cellular connections. It can also be built into stationary devices, such as Amazon’s Echo or Google Home. The question remains can intelligent digital assistants understand the synthesized speech of SGDs?

To answer this question, a preliminary study was conducted and was presented by Dr. Yoo Sun Chung and me at ISAAC 2018. The 6 study participants used a variety of SGDs with 5 different synthesized voices. All 6 participants could “wake up” the intelligent assistant built into their smartphone or their stationary device (Amazon’s Echo or Google Home). Four of the 6 participants who used their smartphones could accomplish all of the tasks once they had programmed the needed requests into their SGDs. The tasks included: (1) call or text the researcher, (2) find the local weather, (3) find a restaurant nearby, (4) retrieve a joke, (5) get information about a specific topic. Two participants used a single-function mobile phone. However, each also used a stationary device that had built-in digital assistants. Using their respective SGD, each still accomplished most of tasks since they had WIFI in their homes.

This preliminary study shows great promise for individuals with complex communication needs who use smartphones and SGDs. A bit of tweaking and pre-programming of these SGDs was necessary so that Alexa, Siri, or OK Google could understand them.

Conclusion

With advocacy we can improve the situation for the 9 million people with speech disabilities in the United States who do not use intelligent digital assistants (Mullin, 2016). What is needed? First and foremost, developers need to expand their speech recognition software to include the “voices” of people with complex communication needs. This includes the synthesized speech software built into SGDs. It may even include recognition of dysarthric speech.

The figure below shows a pictorial history of telephone use from inaccessibility to becoming increased accessibility for those with complex communication needs.

History of Telephone Accessibility

We have come a long way.

We still have a long way to go to attain equal access to information and communication technology.

It has never been more possible than today!

The Future?

Photo of the Future???

Yoo Sun and I would love to hear from you about the potential of intelligent digital assistants for members of the AAC community. We have also developed a handout, What Siri, Google Now, and Alexa Can Do for You. Contact me at dianeb@temple.edu if you are interested in receiving an electronic copy.

References

Bryen, D. N. (2010). Communication during times of natural or man-made emergencies: The potential of speech-generating devices. International Journal of Emergency Management, 7(1), 17-27. doi:10.1504/IJEM.2010.032041

Bryen, D. N., & Chung, Y. (2018). What adults who use AAC say about their use of mainstream mobile technologies. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 12.

Bryen, D. N., & Moolman, E. (2015). Mobile phone technology for ALL: Towards reducing the digital divide. In Z. Yan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Mobile Phone Behavior. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-8239-9.ch115

Bryen, D. N., & Pecunas, P. (2004). Augmentative and alternative communication and cell phones use: One off-the-shelf solution and some policy considerations. Assistive Technology, 16, 11-17. doi:10.1080/10400435.2004.10132070

Bryen, D. N., Potts, B. B., Carey, A. C. (2006). Job-related social networks and communication technology. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22, 1-9. doi:10.1080/07434610500194045

Bryen, D. N., Potts, B. B., & Carey, A. C. (2007). So you want to work? What employers say about job skills, recruitment, and hiring employees who rely on AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2. doi:10.1080/07434610600991175

Bryen, D. N., Slesaransky, G., & Baker, D. B. (1995). Augmentative communication and empowerment supports: A look at outcomes. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 11, 79-88. doi:10.1080/07434619512331277169

Center for an Accessible Society (n.d.). Disability and the digital divide. Retrieved from http://www.accessiblesociety.org/topics/webaccess/digitaldivide.htm

Krupansky, J. (2017). What is an intelligent digital assistant? Retrieved from https://medium.com/@jackkrupansky/what-is-an-intelligent-digital-assistant-3f601a4bb1f2

Morris, J. T., & Bryen, D. N. (2015). Use of mainstream wireless technology by adults who use augmentative and alternative communications. Journal on Technology and Persons with Disabilities, 3, 101-115.

Mullin, E. (2016). Why Siri won’t listen to millions of people with disabilities. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-siri-won-t-listen-to-millions-of-people-with-disabilities/

Wireless RERC (2014). SUNspot–Augmentative and alternative communication device users and mainstream wireless devices. Retrieved from http://www.wirelessrerc.gatech.edu/2014-sunspot-number-01-augmentative-and-alternative-communication-device-users-and-mainstream

—–

Diane Nelson Bryen was professor of Special Education since 1973 and Executive Director of the Institute on Disabilities, Pennsylvania’s University Center for Excellence since 1992 through to her retirement in 2008. She continues to be a leader, mentor, advocate, teacher, and researcher. Her work has been recognized internationally focusing on AAC, criminal justice, inclusive education, assistive and accessible information and communication technologies and Daring to Dream . She facilitates/supports ISAAC’s LEAD Committee.

The author has no financial or non-financial relationships to disclose.

—–

Jill E Senner, PhD, CCC-SLP

SpeakUP

Editor-in-Chief