Teaching Communication Independence

AAC implementation in schools typically focuses on the use of speech generating devices (SGDs) for face to face communication. Ideally, there is a team that collaborates to provide the student with access to core vocabulary and ensure the use of the device across settings. After all, the AAC user needs access to their voice in order to form relationships, participate with their general education peers, and actively engage in learning. We should all be working towards the same goals: access to language, literacy, and communicative independence. But what constitutes independent communication in the world today?

Students Today

As we approach the year 2020, it can be good to examine how typical students engage in learning. This is increasingly mediated by the use of tablets, computers, and other “smart” technology. When my own sons were in high school, they did their research online, used web-based tools to check their grammar, and submitted their work to a virtual classroom. My son, Erik, relied on Turnitin.com. I don’t know that he ever needed to print out a paper and hand in a physical copy.

What Do AAC Users Need to Know?

Should academic participation by AAC users be any different, or require different tools? We also need to keep transition in mind, and plan early. Most post-secondary environments require the use of tools, such as Google Drive, Canvas, or Blackboard. Higher learning requires that the student have background knowledge in the use of these tools. I completed a graduate certificate at Western Carolina University and never once set foot in the state. Sorry, North Carolina! I would really like to visit someday.

The same is true of the workplace. Many jobs require skills that involve online training, distance communication, and the submission of documents using email and other online platforms. At my workplace, we use many web-based tools to share information and stay in contact with the people we serve.

Are AAC users able to participate in virtual environments? Are we teaching them the skills they need before they transition to adult settings? The digital divide impacts many marginalized groups, including people with disabilities. Access barriers exist in the virtual world. We, as educators, can work to minimize their impact.

Some of the Findings

Light, et al (2009) published the findings of a study in which six children were asked to “invent” AAC systems for a peer with disabilities. The children used art materials and their imaginations. The systems they came up with proved to be quite different from those designed by adults. These inventions “integrated multiple functions (e.g., communication, social interaction, companionship, play, artistic expression, telecommunications) and provided dynamic contexts to support social interactions with others, especially peers.” (Light, et al, 2007, p. 274). In this study “the boys’ and girls’ teams both included Internet access in their inventions to support easy use of email, instant messaging, and on-line chat with friends.” (Light, et al, 2007, p.279)

I find it fascinating that these children, all between the ages of seven and ten years, recognized the importance of access to distance communication for the maintenance of social connections. This qualitative study was published twelve years ago, before the near-universal presence of smartphones and social media. I would hazard a guess that a similar study, today, would place an even greater emphasis on distance communication.

In 2009, Gandell and Sutton published a case study where they compared face to face and distance communication between a speaking partner and an adult using Bliss Symbols. An examination of the communicative function of the utterances produced during telecommunication suggested that “the AAC user can exert greater control over the interaction and may encourage more symmetrical use of utterance function” in the telecommunications context.” (Gandell & Sutton, 1998, p.1401). To me, this shows that the AAC user was able to be more of an equal partner in the conversation.

The World Today

Over the past ten years, consumer options for distance communication have increased exponentially. One group that talks about how much they benefit from the use of AAC and distance communication, is that of autistic self-advocates on social media (The people I follow on Twitter choose to use disability first language for themselves). They have spoken about the value of having augmentative communication options when their spoken words are not available to them. This may relate to both in person and distance communication. The use of AAC can decrease communicative pressure, allowing them to cope with novel situations, new people, and less than ideal sensory environments. This can facilitate their engagement in multiple communicative contexts, ranging from ordering a latte at the local coffee shop to participating in graduate studies.

Several of these self-advocates were presenters at this year’s AAC In The Cloud conference. These sessions are available free online by clicking on the link above.

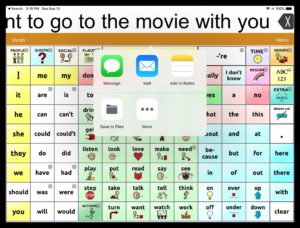

Clearly, there is a need for AAC users to communicate from afar. Fortunately, most devices and apps make this possible. Distance communication is not limited to those who use text-based systems. In TouchChat, Proloquo2Go, and Speak For Yourself (to name only a few), you can take your message and export it to a variety of apps and sites. These include the Notes app, Messaging/texting, Google Hangouts, social media sites, and email. The same is possible with dedicated devices.

TouchChat HD with WordPower and Distance Communication

Challenges for Teaching AAC

In my observation, students using AAC often depend on the help of a one to one, or teacher’s aide, to submit their work. It should be possible for a student to ask a question, give an answer, or write a paper, and send their response directly from their SGD. As we approach the grades in which schoolwork becomes less “hands on”, and written expression is emphasized, our students should be learning to submit their own work, as independently as possible.

A few years ago, I observed an autistic support classroom where an AAC user was working on sending emails to her father. The activity was deeply meaningful, but the emails were being sent from a classroom computer, and not from her device. By using her SGD, she would have had the advantage of established motor plans, as well as knowledge of her vocabulary set and her onscreen keyboard. This could have lessened her cognitive load and let her focus on the content of her message to dad. Her teachers could then have modeled how to export her message.

Speak For Yourself and Distance Communication

How about texting? We might not think this as being a communication modality worthy of academic focus. However, it seems like many teens today use texting as a primary means of communication. My son texts me from college anytime he needs something. Our AAC users need to learn this, too. After all, schools and businesses regularly use text messages to send important notifications and emergency alerts. I know several adults with AAC devices who also rely on texting for social connection. It allows them to stay in touch with loved ones while at work, or in the community.

Having been in the schools, I am familiar with the amount of work teachers have to fit into a school day (spoiler alert: too much). Distance communication skills can be targeted in the context of regular classroom activities. When we work on crafting a text, or sending an email, we are working on language, literacy, social engagement, and access. Universal Design calls on us to offer multiple means of engagement and multiple means to demonstrate learning. Distance communication gives us a socially significant means by which other academic skills can be nurtured.

References:

Gandell, T., & Sutton, A. (2009, July 12). Comparison of AAC interaction patterns in face-to-face and telecommunications conversations. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07434619812331278156

Light, J., Page, R., Curran, J., & Pitkin, L. (2009, July 12). Children’s ideas for the design of AAC assistive technologies for young children with complex communication needs. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07434610701390475

McNaughton, D., & Bryen, D. N. (2009, July 12). AAC technologies to enhance participation and access to meaningful societal roles for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities who require AAC. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07434610701573856

Williams, M., Beukelman, D., & Ullman, C. (2012, June 1). AAC Text Messaging. Retrieved from https://pubs.asha.org/doi/full/10.1044/aac21.2.56

—-

Ms. Helland is the AAC Services Coordinator at TechOWL, part of the Institute on Disabilities at Temple University. She provides information, AAC evaluations and AT consults to consumers of Pennsylvania’s AT Act Program (PIAT). Kathryn is a certified speech-language pathologist and has worked with individuals with autism spectrum disorders and complex communication needs. Kathryn has presented at national conferences, including ATIA, Closing The Gap & ASHA. She enjoys guest lecturing at Temple University and working with the participants in ACES, a transition program for young adults who use augmentative communication. She received her bachelor’s degree from Oberlin College and her Master’s in Communication Disorders from William Paterson University.

Out of curiosity, what was the date of publication for this article? I think it is interesting that the author discusses approaching 2020 and then in 2020 we find ourselves relying heavily on distance learning as a result of COVID-19

October 30, 2019