Happy New Year USSAAC members and guests. We’re ready to start the new year off right with a thought-provoking article by Patricia Politano about strategies we can use to ensure that EVERYONE can communicate.

—–

We can all agree that everyone has the right to communicate, the right to express themselves in the ways THEY choose, and the right to be heard. The Communication Bill of Rights was written by the National Joint Committee for the Communication Needs of Persons With Severe Disabilities (NJC) to include everyone.

But what happens when a person lives in a communisphere where no one notices his or her subtle and/or idiosyncratic communication attempts? What plan of attack is available when people with authority say, “he does not communicate”? Where do we start? How do we change perceptions and expectations?

I need to start by saying that I am a speech-language pathologist and, after 30 years of working in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), I am still learning. I am still discovering new ways of communicating and new ways of empowering people who use alternative communicative methods. My role on an assessment team is always as an outsider, a consultant. The team asks me to provide an AAC assessment, work with the team to collect relevant information, and create a plan to reach the individual’s goals. Even though my perspective is typically as an outsider, I still think the strategies and tools I use could be useful to anyone.

Where to Start?

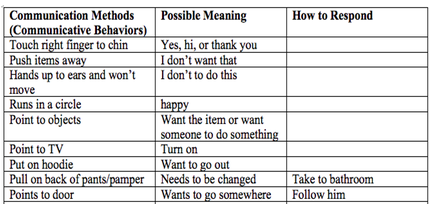

Sample Gesture Dictionary

Gesture Dictionary

I start by trying to learn everything I can about the communicator. I try to find the person or people who know the communicator best. The first tool I typically use is a gesture dictionary. I take out a piece of paper, draw a grid with three columns and say, “Tell me how she communicates.” If there is no response, I continue, “She seems to be more comfortable with you than any of the other staff members. I think it is because you understand her best. I want to take all that knowledge in your head and put it on paper so more people will know how to read her and she will be able to communicate with more people. I know when you watch her, you can tell when she is happy, when she is upset and, or when she needs something or wants something.”

I push on, “In the first column, I want to write down what you see and hear, what she does. Then in this last column, I’ll write down what it can mean.”

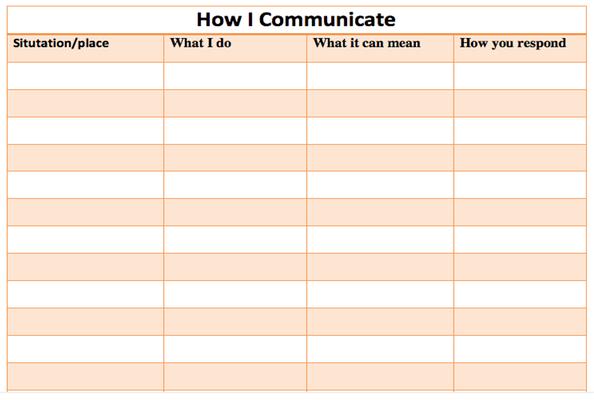

The best gesture dictionaries have detailed descriptions of the communicative behavior(s) so they are easily recognizable, some even include photos of the gestures and made up signals. The more information provided, the better. Some gesture dictionaries will also have a column indicating the situation during which a communication behavior occurs, because the same gesture or behavior could mean something in different contexts. The end goal is to share the gesture dictionary with other potential communication partners so that communication attempts will be noticed and honored by more people. The distributed version should be in first person, “This is how I communicate.”

How I Communicate – Blank Form

A gesture dictionary can be a powerful tool and have a significant impact on an individual’s life when implemented. The truth is, however, that most people are not aware of all the communication behaviors they interpret or respond to. So the gesture dictionary, also referred to as a communication dictionary, is not always easy to create. Some people get stuck on the word communicate and when I try to gather information about how someone communicates, I hear, “He doesn’t communicate. He can’t talk”.

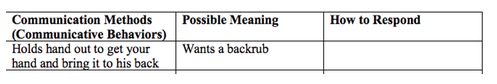

Observation

Sometimes it is helpful if I observe people interacting and then give my feedback. For example, I might point out, “I noticed that when he took your hand and put it on his back, you knew that he wanted a back rub. And you rubbed the spot between his shoulder blades…. I am going to add that to our gesture dictionary.”

Additional items can be added to the Gesture Dictionary following observation.

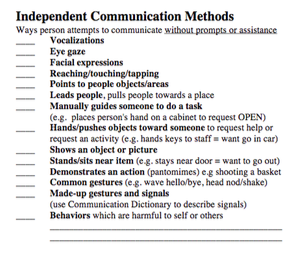

Inventory of Functional Communication

I think it is really important to be as comprehensive as possible. To discover ALL the ways someone communicates and ALL the messages they are communicating. This is how communicators let us know what is important to them. It is the only way I know to attempt to write communication goals that potentially reflect the goals of the communicator.

Many years ago I created an inventory of communication methods and behaviors that can be used in interviews with caregivers and team members. It is called the Inventory of Functional Communication and it is available as free download.

I typically start with the second page of the Inventory which itemizes several communication

This section of the Inventory of Functional Communication is designed to collect information on modes of communication used such as vocalization, eye gaze and facial expression.

methods. I suppose you could give the inventory to a significant other and ask them to complete it, but I believe I get the most information if I go through each item with them. Starting at the top, I say, “Does he make any sounds or vocalizations?” The caregiver might respond, “He makes a sound when he is happy.” I the follow up, asking, “What does it sound like?” Then I write the examples of vocalizations next to the item.

For each subsequent item, I give examples and may pose the question in different ways. I may also add caregiver answers to the gesture dictionary so I am sure to record a functional description of the behavior or gesture or combination of behaviors and what they can mean.

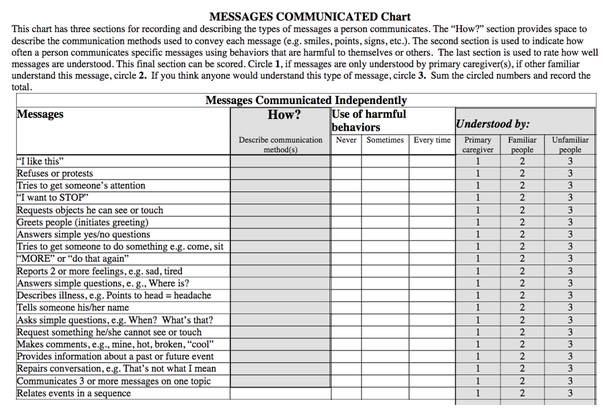

When I think I have exhausted this line of questioning, I move on to the messages communicated page.

Messages Communicated Chart

Personal Communication Passport

Another tool I like to use is a personal communication passport. You can find free downloads for templates at communicationpassports.org and a Google search will lead you to Pinterest sites with a wide variety of ways to personalize a communication passport. Most important is that the communication passport provides a way to share more relevant information beyond the gesture dictionary. A communication passport will include the people, things, and topics that interest the communicator most. It also includes information about the communication aids used and the supports that may be vital for successful interactions.

Use of any of these tools and strategies can help us hear the voice of communicators who use subtle and idiosyncratic communication methods and help us honor the communication rights of everyone. More importantly, these tools provide a way to share someone’s communication system with the people in their communisphere so that they can have successful interactions with more people. These tools can also be used to identify functional communication goals, but I think I will leave that topic for another blog.

References

Communication, Access, Literacy, and Learning (CALL Scotland). Personal Communication Passports https://www.communicationpassports.org.uk/Home/

National Joint Committee for the Communication Needs of Persons With Severe Disabilities. (1992). Guidelines for meeting the communication needs of persons with severe disabilities [Guidelines]. doi:10.1044/policy.GL1992-00201

Politano, P. (2012). Inventory of Functional Communication. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272417253_Inventory_of_Functional_Communication

—–

Patricia Politano, PhD, CCC-SLP/L, is a speech-language pathologist that has worked as an AAC specialist for over 25 years at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Assistive Technology Unit. She is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Disability and Human Development and teaches courses for the UIC Assistive Technology Certificate Program. Dr. Politano presents nationally and internationally on augmentative communication and the rights of people who use AAC. She has no financial relationships to disclose. Nonfinancial relationships include authoring the Inventory of Functional Communication.

—–

Jill E Senner, PhD, CCC-SLP

SpeakUP

Editor-in-Chief