AAC Awareness Month has officially ended, however SpeakUp will continue to share information and resources throughout the year in the spirit of USSAAC’s mission to promote the best possible communication for people with complex communication needs. Today we welcome Andrea Kremeier and Kristy Weissling, guest authors from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, who offer this informative post with suggestions for implementing AAC with people who have aphasia.

Aphasia is an acquired communication disorder that can occur with a stroke, brain injury or other neurological disorder. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), “Aphasia may cause difficulties in speaking, listening, reading, and writing, but does not affect intelligence.” Providing AAC services to individuals with aphasia can be a daunting task for even the most experienced speech-language pathologists (SLPs). It is helpful to remember that AAC is the implementation of any strategy that helps a communicator convey a message. This broad view of AAC opens the door for many no-tech and low-tech strategies that clients and clinicians are already using. These approaches are particularly effective in individuals who have severe aphasia. The National Aphasia Association has coined the phrase “loss of language not intellect,” which makes the need to find ways to reveal an individual’s intellectual abilities all the more important.

No-tech, unaided strategies may already be in place. These include the use of gestures, facial expressions, head nods/shakes, self-made signs, and even non-speech vocalizations (e.g., using prosody to convey someone’s mood). The clinician in the role of “coach” can help the person with aphasia expand, adjust, and sharpen these natural abilities. Skills that are self-initiated by the person with aphasia are often the most salient and effective strategies. Clinicians should carefully observe the communication patterns of people with aphasia and coach them in ways to advance these skills.

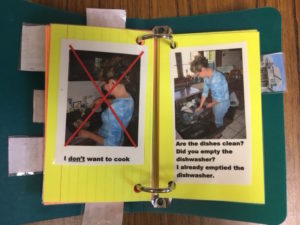

There are a variety of low-tech AAC strategies. These approaches may be as simple as pictures in a picture album or the use of clinician-generated materials such as alphabet boards, individualized

individualized communication book containing pictures

communication books containing pictures, low-tech visual scene displays, or rating scales. Other examples of low-tech strategies include the use of written scripted conversations, pre-written information, family trees for remembering names, maps to denote locations or direction, checklists, objects, graphic scales (e.g., Likert scales for how much something is liked or a pain scale for denoting comfort level), and written choice communication (Garrett & Beukelman, 1995). Some people with aphasia retain the ability to produce word fragments. They may write a word with enough similarity to the target that the communication partner comprehends the meaning. These written words can be retained in an active writing notebook and used later for reference (eliminating the need to re-write the content). If these words are used often they can be added to communication aids for more permanent use.

The combination of strategies and their frequency of use will be unique and highly tailored to each individual with aphasia. The role of the SLP is to coach the person with aphasia (and their communication partners) in maximizing the use of these strategies. It is easy to fall into the trap of one strategy for one situation, but the truth is that multiple strategies should be used at a time in any given situation. With one verbal statement, a person without aphasia might use both no-tech and low-tech AAC to supplement verbal communication. For example, a husband rushing his wife out the door might simply say, “Come on, it’s time to go.” On the surface, it might seem that he isn’t using any augmentative strategies. However, he augments his spoken message as he gestures for her to come and points to his watch, as his intonation conveys his impatience, and as his facial expression shows exasperation. Similarly, a person with aphasia will likely need to use multimodal communication to express intent. It is the SLP’s job to help the person with aphasia determine what types of no-tech, low-tech, and high-tech communication they are able and willing to use to most accurately convey a message. For some, the use of positive and negative facial expressions may be more reliable than a verbal yes/no response. For another, carrying paper around to write down fragments of words may help to facilitate a conversation around a topic. Some people with aphasia may benefit from various types of high- tech AAC including dedicated systems or tablets with apps. Each individual is unique.

When approaching decisions about AAC strategies it may be helpful to consider whether the client is a partner dependent or independent communicator (Garrett & Lasker, 2013). Checklists may assist the clinician in making this decision (http://cehs.unl.edu/documents/secd/aac/assessment/aphasiachecklist.pdf). Strategies most appropriate for partner-dependent communicators include:

- Augmented Input

- A communication partner supplements spoken language with gestures, writing or drawing to help the individual with aphasia to better understand what was said.

- Written Choice Strategy

- The communication partner asks a question and then writes down words or phrases to allow an individual with aphasia to respond by pointing to his or her desired response.

- Tagged Yes/No Questions

- A communication partner asks a yes/no question and then adds a verbal and gestural yes or no at the end of the sentence. For example, “Do you like pizza, yes [nod] or no [shake head]?”

- Experiment with Stored Messages and Visual Scenes

- In some cases transitional communicators may begin to try visual scene displays and other forms of message storage techniques.

Strategies for independent communicators include pre-written information, low-tech/high tech visual scene displays, individualized communication books, and potentially, high-tech AAC systems with activity and in some cases special cases semantic/syntactic displays.

The SLP’s primary goal is to reinforce that everyone communicates at their highest possible level, every day. That’s the central tenant of AAC and aphasia assessment and interventions. People should not have to “wait” to communicate until they are in a different setting, have different partners, or have recovered some skills. Helping a client communicate from the start of their journey with aphasia may help them to continue to build their life narrative. It may also empower an individual to live successfully with aphasia. Participating as an active contributor throughout the course of an individual’s treatment plan and actively engaging in health care decisions is important to everyone, including people with significant communication needs. This is the core of patient–provider communication and it applies to people with severe communication disabilities as well as to those with less severe communication disabilities.

Everyone communicates every day!

References

ASHA. Aphasia. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/Aphasia/

Garrett, K. L., & Beukelman, D. R. (1995). Changes in the interaction patterns of an individual with severe aphasia given three types of partner support. Clinical Aphasiology, 23, 237-251. Retrieved from http://eprints-prod-05.library.pitt.edu/204/1/23-20.pdf

Garrett, K. L., & Lasker, J. R. (2013). Adults with severe aphasia and apraxia of speech. In D. R. Beukelman & P. Mirenda (Eds.), Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (pp. 405-445). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

—-

Andrea Kremeier received a Bachelor’s of Science in Education with an endorsement in speech-language pathology from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. She is currently in her second year studying speech-language pathology as a graduate student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Kristy Weissling, SLP.D., CCC-SLP, is an Associate Professor of Practice at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She received her B.S. and M.S. from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She received her professional doctorate in speech language pathology from Nova Southeastern University in 2006. She is the on-campus clinic coordinator, SLP program coordinator, and is one of four investigators on the NIDILRR Grant titled: Optimal Augmentative and Alternative Communication Technology for Individuals with Severe Communication Disabilities: Development of a Comprehensive Assessment Protocol. She has 27-years of experience as an SLP. Her most specific expertise is in the area of Augmentative and Alternative Communication for individuals with acquired neurogenic communication disorders. She has been an author of peer-reviewed journal articles, text book chapters, and national and international peer-reviewed presentations.

—-

Jill E Senner, PhD, CCC-SLP

SpeakUP

Editor-in-Chief