by Deirdre Galvin-McLaughlin M.S. CCC-SLP

Physical prompting is a set of prompting techniques that can be used for teaching of new motor, technology, and communication skills. It involves the prompter (e.g. therapist, teacher or family member) providing direct physical guidance to the learner in order for the learner to complete the skill. While physical prompting may also be used to teach the production of signs, this blog post refers to physical prompting that is utilized when using augmentative and alternative communication systems and speech-generating devices. For people who use their hands to access technology, the prompter’s hand is placed on top of (“hand over hand”) or under (“hand under hand”) the learner’s hand to guide them in selecting a symbol or button. In the case of alternative access, the prompter guides the learner’s hand or other body part towards the technology (e.g. switch) or target to result in a selection.

Within a given type of physical prompt, there are different levels of support based on how much the prompter contributes and how much the learner contributes to the completion of the targeted skill (Bean, Williams, Cargill, Lyle, & Sonntag, 2021). Some rate physical prompting as ranging from total support as defined as “the learner expends less than 25% of the effort to complete the motor task, while the clinician provides 75%–100% of the effort” to minimal support as defined as “the learner expends 75%-100% of the effort to complete the motor task, while the clinician provides less than 25% of the effort” (Bean, Williams, Cargill, Lyle, & Sonntag, 2021).

Clinicians who work in AAC may struggle with the ethics of providing physical prompting to learners who are developing emerging skills. Some fear that physical prompting is too similar to the debunked approach of facilitated communication (FC) whereby a “facilitator” knowingly or unknowingly authors the message by using the person’s hand as a tool to type or spell messages. More nuanced approaches that resemble FC, like the rapid prompting method (RPM), often include a “prompter” that guides the authorship of the message by rapidly issuing spoken, visual, and physical prompts that influence the letter by letter spelling of messages written by or with the learner. RPM differs from FC as direct physical guidance is not consistently utilized for all learners. These approaches do not have a prescribed method whereby a prompter deliberately and systematically fades out this type of support. Both the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) and the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (ISAAC) have issued statements that facilitated communication and rapid prompting methods are NOT evidenced-based methods and should not be used by speech-language pathologists (ISAAC, 2014; ASHA, 2018). Additionally, some clinicians are concerned that they are taking away autonomy of the client by physically guiding them to selections or messages and are conscious of respecting both body and communication autonomy.

Most clinicians agree that having a system that does not require any prompting by an assistant or family member is the ultimate goal for an AAC system, and providing the most amount of control to the user in selecting the symbols, words, and letters in their system is paramount. However, many struggle with identifying the “right amount of support” to provide a learner when they are learning to use an AAC system. This post was inspired by questions that the USSAAC board of directors and members receive about this matter, and USSAAC offers this review of current considerations and guidance for our community.

To investigate this question, we did a deep dive into current practices, research, and opinions to answer a few questions.

- Should clinicians use physical prompts at all in AAC?

- When is it appropriate to use physical prompts?

- If I can use physical prompts, how often should I provide them?

- How should I approach using a physical prompt with a client if I want to use this strategy?

We started our investigation by considering all the ways physical prompts could be provided by clinicians for AAC and what traditional forms have been used and encouraged as a strategy. We attempted to define these here as a way of coming up with common terms to talk about physical prompting during facilitated communication and rapid prompting methods and outside of those approaches.

Physical prompts

Physical prompts are an umbrella term that includes any physical guidance to activate a message. This is used in order to capture prompting that might be used for people who do not use their hands to access their communication system. Traditionally, physical prompting was thought to be synonymous with hand-over-hand prompting but it also includes hand-under-hand prompting and directly guiding body parts to access technology (head, arm, feet etc.). This is different from a touch or tactile cue (like tapping a shoulder for attention) that is primarily used to direct attention rather than to physically guide a learner to complete a skill.

For people who use their hands…

Hand-over-hand prompting involves a prompter putting their hand over the learner’s hand. Sometimes this involves just guiding the hand to the screen or page to initiate a selection and sometimes therapists will use their hand to isolate a person’s index finger into a point from the rest of fingers. This type of physical prompting gives the prompter complete control over the physical selection of a message.

Hand-under-hand prompting involves a therapist putting their hand under a learner’s hands to guide them towards a selection on a page or screen. In this type of physical prompting, the learner can more easily release their grasp from the therapist. For learners who experience blindness and vision impairment and access their environment using touch, this type of guidance may be used to guide the learner to a target so they can feel it with their hands.

See video below by the National Center on Deaf-Blindness from their “Open-Hands, Open Access modules” for a more in depth explanation and example of how children with sensory impairments observe with hand-under-hand support.

Another video example from the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired Outreach program demonstrates how hand-under-hand support is used in a cooking routine with a child who experiences a sensory impairment. Note how the child will release their hand to take breaks and the hand-under-hand guidance is deliberately used for participation and teaching of steps in routine.

https://library.tsbvi.edu/Play/53

What about for people who don’t use their hands…

There can still be physical guidance by a therapist. It looks differently. Therapists may physically guide a person’s head towards a paddle on a head array to activate a switch. Therapists may physically hold up a person’s head to support exploratory eye gaze activations on an eye gaze device or eye gaze frame.

Next let’s talk about facilitated communication and rapid prompting methods

Facilitated communication is defined by Schlosser and colleagues (2015) as “a technique whereby individuals with disabilities and communication impairments allegedly select letters by typing on a keyboard while receiving physical support, emotional encouragement, and other communication support from facilitators.” In facilitated communication, the communicator relies on an assistant for physical prompting to spell messages letter by letter. Often this involves the assistant using the communicator’s hand as a tool to select messages with hand-over-hand support. There is no plan to fade use of the assistant over time.

Rapid prompting method often involves the use of multiple strategies to quickly prompt a user to spell a message. These strategies are often direct physical guidance of the learner’s hand, spoken prompts, pointing to targets, and moving the device or display so the learner’s hand lands on a target.

Both methods have been found to have no scientific evidence for effectiveness in AAC in systematic reviews by Schlosser and colleagues in 2015 and 2019.

This in-depth presentation for the National Council on Severe Autism in 2021, entitled “What’s wrong with Facilitated Communication” by Ralf Schlosser, Howard Shane, James Todd, and Janyce Boynton, describes the risks associated with Facilitated Communication and Rapid Prompting Method as well as ways to assess facilitator influence. Please review to learn more.

What are the potential harms of physical prompting?

We know that clinicians have concerns about using physical prompting because of the potential risk for harm to clients if misused or used inappropriately. This list does not encompass all potential risks but does highlight many that are cited when physical prompting is used.

- Prompt dependence: an individual becomes reliant on a partner to be successful at completing tasks. Individual may play too passive of a role and may not be actively learning

- Control over authorship of message: partner influences too much control over the autonomy of a message as seen in FC or RPM

- Consent: individual may not be able to express consent or refusal to physical prompting

- Bodily autonomy: individual may not want to have body controlled by another person

- Communication autonomy: individual use of body language to communicate that they do not want to imitate a selection or initiate a selection may be violated in favor of using a device or completing a therapy goal

Why do clinicians use it then when there are harms?

Clinicians try to scaffold towards attainment of goals by providing varying levels of assistance with the ultimate goal being for the individual to achieve the goal independently. Sometimes for individuals learning new skills this involves providing initially maximal levels of assistance to complete a goal. Maximal levels of support range from modeling a selection to hand over hand support. Some clinicians do not feel comfortable providing physical support given potential concerns and elect not to use it in favor of other methods.

So to get back to our original purpose and answer our main questions…

Should clinicians use physical prompts at all in AAC?

From reviewing the research, clinicians can use physical prompting in some cases after exhausting other methods of prompting and accommodations to activity or task demands that may increase the individual’s independence towards achieving a goal. However, this level of support should be carefully considered and restricted given the potential harms associated with it.

We suggest clinicians consider the following before using a physical prompt..

- Am I planfully implementing a least-to-most approach to prompting (see section below for more information on this approach)?

- Have I sufficiently modeled how to select symbols or words on a device in a way that is accessible for the individual?

- Have I used the device in a motivating context that the individual is interested in and attentive to?

- Does the individual demonstrate signs of wanting to communicate with the device but has trouble with accessing the device?

- Does the client use body language to communicate that they are not interested in activity, goal, or communication tool?

- Have I tried to support someone to physically access the device in a context that does not include communicating a message as a way to explore using the system but not controlling communication/message autonomy?

- Does the system that we are using best meet the needs of the individual or should we try other settings or systems that may make accessing the device easier?

- Are there other factors that can be accommodated in the environment that may influence the individual’s ability to attend to or use the system?

So when is it appropriate to use physical prompts?

The guidance suggests that physical prompts may be used in isolated instances after adjusting all other factors for teaching new motor skills or generalizing an existing motor skill to a communication context.

For example, some children who can use a switch to activate an adapted toy or a single message voice output communication device may require some initial support to activate a switch in scanning on a speech generating device given new learning demands of timing and inhibiting repeat activations. A clinician may assist initially with physical prompting in this context to teach unique timing associated with this aspect of motor learning. To minimize the influence of choosing a message and increase the excitement of activity, a clinician may do this in a switch accessible computer game or activity.

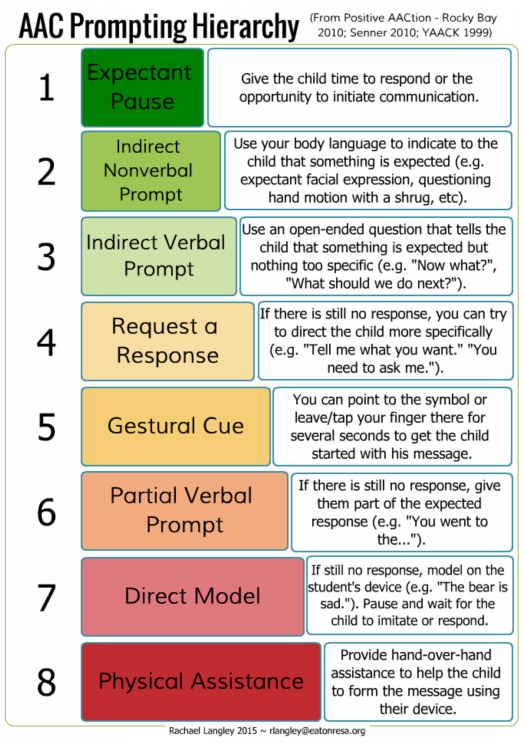

Some suggest that a least-to-most prompting hierarchy should be used in therapy with wait time between each step. A least-to-most prompting hierarchy starts by eliciting new skills using minimal then moderate then maximal prompting with added-wait time in between each step. Depending on the skill, this hierarchy can appear differently but we’ve included an example of a schematic illustrating examples of least to most to serve as a guide.

AAC Sample Prompt Hierarchy by Rachael Langley (2015) featured in blog post by Speak Up. Link to post included below for more resources –

If I can use physical prompts, how often should I provide them?

The guidance suggests that the frequency of physical prompts should be minimal for greatest promotion of independence and to reduce potential harm to the client. Clinicians should reevaluate use of physical prompting if the client does not make progress towards independence following several trials. Consideration of environment, motivation, health factors, device appropriateness, device setting appropriateness may identify the real obstacle to independence rather than the need for physical support to learn a new skill.

How should I approach using a physical prompt with a client if I want to use this strategy?

All clinicians should first and foremost respect the client’s autonomy. This includes bodily autonomy and communication autonomy.

When thinking about the choice to use physical prompting, it’s important to consider how you would feel if you were in the client’s situation.

Below are some prompting questions to consider this from a client’s perspective:

- Would you be ok if someone just started putting their hand on your hand to make a choice?

- How would you want a clinician to approach this with you? What would make you feel more comfortable?

- How would you want to be able to get out of a situation if you didn’t like someone providing you physical prompting?

- If you were not able to make a clear communicative response via body language that you did not like the level of support, would you want someone to attempt physical prompting in the first place?

Some ways to approach the use of a physical prompt that respects the autonomy of your client is also included below for reference

- Ask for permission and if you can help them use their hand or body part (head, foot, knee etc) to access the target. Provide sufficient wait time for response.

- Before providing a physical prompt, use plain language to describe how you are going to help them access the target.For example, say “I’m going to move your head to show you how to make a choice” or “I’m going to move your hand to show you how to choose”.

- When providing a physical prompt, consider providing the least restrictive or least amount of a physical prompt. This may be providing hand under hand support so that a person can release easily from your grasp rather than providing support where you are preventing a person from removing their hand or body part.

- If a person communicates to indicate that it wasn’t welcome, honor that intent and provide a clear communication response acknowledging their choice and apologizing for making them comfortable (e.g I’m sorry, it was clear that you don’t like me touching your hand. We won’t do that again).

Conclusion

Clearly, this is not necessarily an “all or nothing” issue, and it is one where more research specific to communication could be beneficial. Our hope is that clinicians consider all the potential risks and benefits of using physical prompting and use a least restrictive approach to working with clients. Clinicians should plan how to fade support and what other factors external to the client may be influencing the skill. This is not a blog specifically in favor of or against physical prompting, but a blog that acknowledges that, on a case-by-case basis, physical prompting may be used to work towards motor or communication skills.

Do you have questions, thoughts or concerns about physical prompting? Comment below or email us with your thoughts. We’d love to hear from our community!

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2018). Facilitated communication [Position Statement]. Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy. doi:10.1044/policy.PS2018-00352

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2018). Rapid prompting method [Position Statement]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/. doi:10.1044/policy.PS2018-00351

Bean, A., Williams, W., Cargill, L. P., Lyle, S., and Sonntag, A. M. (2022). Systematic Physical Assistance During Intervention for People who Use High-Tech Augmentative and Alternative Communication Systems: The Importance of Using a Common Vocabulary. JSLHR. 45(6): 1592-1596. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_JSLHR-21-00421

Finke, E. H., Davis, J. M., Benedict, M., Goga, L., Kelly, J., Palumbo, L., Peart, T. and Waters, S. (2017). Effects of a Least-to-Most Prompting Procedure on Multisymbol Message Production in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. AJSLP. 26(1): 81-98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_AJSLP-14-0187

International Society on Augmentative and Alternative Communication (2014). Facilitated Communication [Position Statement]. https://isaac-online.org/wp-content/uploads/ISAAC_Position_Statement_March-18.pdf

Libby, M. E., Weiss, J. S., Bancroft, S., & Ahearn, W. H. (2008). A comparison of most-to-least and least-to-most prompting on the acquisition of solitary play skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1, 37– 43.

Schlosser, R.W., Balandin, S., Hemsley, B. Iacono, T., Probst, P, and Von Tetzchner, S. (2014). Facilitated communication and authorship: a systematic review. Augment Altern Commun. 30(4):359-68. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2014.971490.

Schlosser, R.W., Hemsley, B., Shane, H., Todd, J., Lang, R., Lilienfeld, S. O., Trembath, D., Mostert, M., Fong, S., & Odom, S. (2019). Rapid Prompting Method and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review Exposes Lack of Evidence. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 6, 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00175-w

Schnell, L. K., Vladescu, J. C., Kisamore, A. N., DeBar, R. M.,Kahng, S., & Marano, K. (2019). Assessment to identify learner-specific prompt and prompt-fading procedures for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 53(2):1111-112. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.623 C

About the Author

Deirdre Galvin-McLaughlin, M.S. CCC-SLP, is a speech-language pathologist in the Jay S. Fishman Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Augmentative Communication Program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She is also a clinical instructor at Boston University where she started a new infant-toddler AAC program for clients with complex medical conditions. She has expertise in AAC with clinical interests in supporting people who experience motor or sensory access challenges to traditional forms of technology. She previously worked as as a research associate in the REKNEW lab under the direction of Melanie Fried-Oken to develop a brain computer interface for AAC, as a speech-language pathologist in the OHSU CDRC Assistive Technology Clinic, as a research associate on the Communication Matrix, and as a board member on the Go Baby Go Oregon committee. She is currently a member of the board of directors for the Communication Matrix Foundation and the Editor-in-Chief of Speak Up! a blog by USSAAC. In her spare time, Deirdre loves to hike and run with her husband and their rescue pup.

We should not be touching AAC users during communication attempts, including using hand-under-hand, moving the head or limbs or holding a head up during eye tracking. And any touch of the body violates autonomy and can influence and override the communication intent or the AAC user. With some very limited exceptions such as Deafblindness in very limited situations touching AAC learners and users is unacceptable. The rates of abuse for the disabled, plus the negative impact of the prompter influencing communication, in addition to the evidence that passive observation is more effective than physical prompting all back the decision to take physical prompting off of our hierarchy in aac. http://teachinglearnerswithmultipleneeds.blogspot.com/2016/03/rethinking-aac-prompting-hierarchy-in.html?m=1

Thank-you for such a thoughtful blog post. I am often concerned about the unintended message of inherent in the use of physical prompts, the message that other people have the right to control your body or have access to your body. I worked with adults who had been institutionalized (at the Willowbrook Developmental Center in NY), most of whom had been abused. We struggled to provide therapy, especially developing appropriate means of communication, while being keenly aware of where our hands were at all times. The risk of unintended consequences from the (over)use of physical prompting is real.

This essay further perpetuates misinformation about FC and RPM written by people who have never used the techniques and who willfully misrepresent them in the published literature and then work with professional societies to use the misinformation and manufactured criticisms to write policies that disparage them and the people who use them to learn the motor skills to type imdependently. The people like Schlosser, Helmsey, Shane and Todd are not well intentioned or honest, but the people who quote them often are. People who use AAC can (and do) speak for themselves about what is helpful in learning to overcome motor challenges, and we need to listen to them–not to the people who claim to “be the voice of AAC”

I do not use FC/RPM/S2C with my nonspeaking family member. The resources you used in this post are concerning. The NCSA has a bias towards using inflammatory and derogatory language towards autistic people, people with intellectual disabilities, and disabled people with high support needs. They also promote segregated settings for disabled people with high support needs. The NCSA also does not create any discussions around actively promoting robust AAC with disabled individuals. At least one of the presenters in the NCSA webinar promotes behaviorism. Behaviorist teaching methodologies have a long history of gatekeeping robust communication options for nonspeaking autistic people. Behaviorists also promote segregated settings, they actively discourage nonspeakers from having access to general education curriculum with necessary adaptations if needed, and heavily contribute to the massive education neglect in this population. FC/RPM/S2C are just the symptom of the larger problem of the continual segregation of disabled people and sheer educational neglect of a very underserved population. Please find resources that better promote robust AAC, autonomy , agency, and access to full comprehensive literacy instruction. I would cut ties with any resources that ally with behaviorism and ABA as several external metanalysis studies have shown that they have a very large body of ‘low quality’ scientific evidence and therefore have a weak evidence base to support their own claims. I suggest the Comprehensive Literacy for All framework as a great place to start.