Today we are pleased to welcome back Vicki Clarke for Part II of a her series on AAC in English as a Second Language learners (ESL).

—–

In Part I, the challenges bilingual families and people who use AAC were discussed along with the research on this subject. The overall conclusions were that, “The research consulted seems to clearly indicate that encouraging and promoting a student’s language and augmentative communication in both their native language and the language of their local community is our best practice.” Today we will explore options for individuals who use AAC who are bilingual as well as the implications for AAC use.

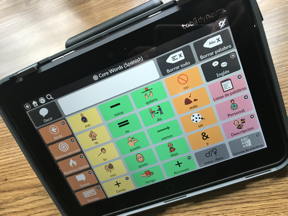

With a push of an onscreen button, a Spanish page will load.

Now the individual can communicate in Spanish.

Several speech generating device manufacturers offer page sets in different languages with multiple voices. Many of them offer bilingual page sets specifically for Spanish speakers. Tobii Dynavox and Prentke Romich both offer Spanish bilingual page sets. These allow the AAC user to toggle between English and Spanish. The first time I showed this feature to one of my bilingual students, Gabriella, she gave me a huge grin, grabbed the device, and proceeded to teach me a lesson in Spanish. Even with limited Spanish knowledge, this feature has allowed me to successfully conduct AAC evaluations with my bilingual students. Without fail, the student’s reaction to hearing their home language coming from the device is overwhelmingly positive and excited.

The NovaChat family of devices offers an option to set up different “profiles” so that users can have an English speaking page set and an identical page set that speaks their native language. Speech pathologist Chelsea McCown’s student is using a custom 4 location pragmatically organized page set she has created in both English and Spanish. She saved a “profile” in each language that uses the corresponding language in the menus, voice, words, and settings. This allows the family to understand and model for their child using Spanish on their system and to make their own modifications and to support their own English learning.

Be sure to teach the person using AAC how to switch between their two languages!

Training and Support Concerns:

Explaining the use of an AAC system, modifications, and partner strategies can be challenging, even without a language barrier. In our schools, I often don’t have easy access to the families and consequently struggle to do this training for most of my students. For our bilingual students, this is even harder. Here are a few suggestions to help train and support families:

Invite an interpreter to join you for all trainings. Be sure to provide training materials written in the family’s native language. In a pinch, you can use Google Translate for free, but you may want an interpreter to proofread your documents, as the translations can be impacted by local dialect.

Be aware of any cultural habits or customs that may impact your interactions. Some cultures are very reticent to make demands of perceived authority figures, such as teachers. They may hesitate to demand the accommodations they need related to their language barrier. Don’t just accept their gracious refusal of assistance without being sure they understand your willingness to help and exactly what you are offering. We have found that showing families their options is usually more explanatory than just describing the bilingual page set.

Implications for All AAC Learners (BICS & CALP)

We know from bilingual language learning theory (J. Cummins, 1984) that it can take from 6 months to 2 years for bilingual speaking students to learn Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS). These are surface level language skills often comprised of typical social niceties, and context based, familiar requests and comments. For me, these include messages like “Hola!” (Hello), “Como esta?” (How are you?), “Muy bien” (Very good), “Adios” (Goodbye) and “Dónde está el baño?” (Where is the bathroom?). I still find myself hesitant to use these few phrases, even though my execution is fairly stellar, because the inevitable response from my conversational partner is almost always beyond my rudimentary Spanish knowledge.

This fear of communicating in a new language (including the use of new AAC systems) is widespread. Last year, a young bilingual mother met with me for her first training on her child’s new communication device. I advised her to spend a lot of time initially just talking to her son using the device (Aided Language Input) so that he could see how communication worked using this new tablet. As she listened to me, she nodded knowingly. “When I moved to this country 13 years ago, I did not speak to anyone in English for over a year. I was afraid to make a mistake and sound foolish!” She chose to listen, without speaking, as she began to learn the language of her new community. Our AAC users often feel that same fear of failure. They hesitate because they don’t have sufficient experience watching how AAC works in the real world. Aided language input is a research-based method to give the AAC user exposure without pressure.

I find in practice; this basic conversational and simplistic language is a great place to start with all of my AAC users (bilingual and English speaking). Cummins tells us that without these skills, bilingual users cannot be expected to gain the next level of language learning, Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP). His theory informs us that achieving language proficiency in academic subjects can take from 5-7 years for bilingual students. When we consider our targets for AAC users, starting with academic language/vocabulary goals is likely to lead to frustration and failure, for ALL of our students using AAC. Let’s make sure we have our BICS under control before we expect responses to quizzes!

Assessing, supporting, and augmenting the communication of bilingual students is challenging. It seems that we are just beginning to see sufficient research to guide our daily practice. The main goal is to simply keep trying; to be diligent as we ensure that our families understand us and understand their choices; and to guarantee that bilingual people using AAC are not limited to communicating in only one of their languages!

References:

Soto, G & Yu, B. (2014) Considerations for the Provision of Services to Bilingual Children Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30:1, 83-92, DOI: 10.3109/07434618.2013.878751 Accessed on-line https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2013.878751

Cummins, J. (1989) A Theoretical Framework for Bilingual Special Education, Exceptional Children, 56:2, 111-119. Described on-line at http://esl.fis.edu/teachers/support/cummin.htm

Cummins, J. (1984) Bilingual Education and Special Education: Issues in Assessment and Pedagogy, San Diego: College Hill Described on-line at http://esl.fis.edu/teachers/support/cummin.htm

—–

Vicki Clarke is the CEO of Dynamic Therapy Associates, Inc (DTA Inc.), a speech language pathology clinic specializing in AAC. She is the Director of DTA Schools, a division of DTA Inc, which provides individual student, classroom and district-wide AAC services for consultation, assessment, training, curriculum development and equipment procurement in multiple public school districts. Additional professional activities include professional consultation and training through publications, workshops and presentations at local, state and national conferences in the areas of augmentative communication, speech language pathology, special education and Autism.

Mrs. Clarke has no relevant financial relationships to declare.

—–

Jill E Senner, PhD, CCC-SLP

SpeakUP

Editor-in-Chief