AAC Awareness Month has ended but SpeakUP will still continue providing thought-provoking posts. We are excited to share today’s innovative guest post by Chris Bugaj. Computer programming is becoming part of the curriculum in many states but how does this apply to those using AAC? Read on for his take on “coding for core.”

—–

A young girl holds an iPad in her hands. Her friend is pointing over her shoulder at something on the screen. Listening to her friend, she drags a puzzle piece to drop in line with a series of others. Collaboratively, the two are arranging the pieces, snapping them together vertically, linearly, and sequentially. When they’re finished, one says, “Let’s try it” and the other presses a button. Their faces light up as the toy robot nearby lurches forward, following the commands they just created.

“Eureka! It works!”

The two girls used block coding to create a program. They then sent that program to the robot which, in turn, followed the command. It wasn’t perfect at first, but after some trial and error, multiple discussions, and a dash of determination, they reasoned out what they needed to do to make the robot perform the way they wanted.

Could one of the girls be a user of augmentative or alternative communication (AAC)? Imagine Samantha, a 5th grader without a disability, working alongside Rhea, a classmate who uses AAC, to build the code that commands the robot. Imagine Kelvin, an 8th grader with autism who uses AAC, using his device to communicate with his non-disabled peers while working on a coding project in his science class. Imagine Max, a 2nd grader with a language delay whose primarily form of communication is verbal speech working on his language goals by programming a robot or video game that Ms. Ulrich, his SLP, uses in therapy with other students, including Dhairya, a student in preschool who is just beginning to learn to use his AAC device. In any of these scenarios, the act of coding is helping to teach language to users of AAC.

Coding In The Curriculum

In 2017 the Virginia Department of Education adopted Computer Science student standards. Other states, including Ohio, Utah, Wisconsin, and Idaho all have efforts to integrate computer science into every day education. These states have recognized that coding is a skill that citizens need to possess in the future, just like reading, writing, and arithmetic. Knowing the fundamentals of coding can lead to future employment opportunities as well. Contemporary educators in these states are being expected to design experiences for students (including those using AAC) to learn the basics behind coding and programming.

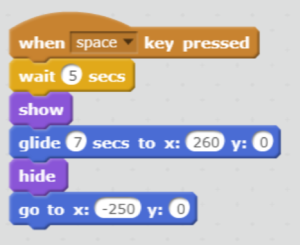

Block-based programming, also known as Block Coding derives its name from a user interface that allows people to build computer programs by simply dragging and dropping color-coded puzzle blocks around on a screen each representing a specific command in the program. There are multiple free coding applications that use color coded, puzzle-like pieces to help learners (of all ages!) begin to understand the basics of programming/coding. Scratch is probably the most well-known.

Block coding screen shot.

Each puzzle piece represents a command, like move forward, stop, turn, grow, repeat, etc. Users drag the puzzle pieces around to create different sequences which control objects. The objects can be digital (called sprites) or real, like a robot. In a very basic example, a student could tell the object, like a digital image of a ball or a tangible robot that looks like a ball, to roll forward 10 inches, stop, turn left, move ahead 10 more inches, change colors (or light up), play a sound, and so on.

When first starting, users are given very easy challenges to accomplish, like sequencing a few puzzle pieces to produce a desired or prescribed effect. You can try some here to get an idea of how lessons build upon one another to grow in complexity as users develop their skills. Eventually, users become so proficient they can create code to accomplish just about anything they can imagine! The possibilities are truly endless.

Schools which have begun to implement coding might do so by introducing daily lessons. Students in special education settings and those using augmentative/alternative communication devices should be included in these lessons and provided an opportunity to learn to code as well.

Language and Coding Symbiosis

Language and coding are linked; two sides of the same coin. They are both ways to communicate using a structured rule set. Language itself is the code humans use to engage with one another. Providing a learner an opportunity to code can help them to see the relationship between the specific command and the resulting object interaction. This can then spur the similar connection of how the use of specific words can cause reactions in other people. For example, a student can correlate that programming a robot to go is similar to asking a person to go. The command “go” results in the same reaction from the robot and the person.

The idea of teaching all students, no matter their language, cognitive, or physical abilities, to code provides an extraordinary opportunity for educators working with students who are using AAC devices to learn language. Educators can use block coding as an engaging way to teach language using contemporary tools while simultaneously teaching the students who use AAC how to code. Learning language through AAC devices and learning to code has a natural synergy. What follows are examples of different ways to implement coding in educational or therapeutic lessons:

Coding to Learn Core (and Fringe) Vocabulary

Experiences can be designed where all learners are invited to code to learn vocabulary, especially core vocabulary. The basic commands for coding include terms such as move, turn, say, think, show, hide, go to, go back, play (a sound), repeat, wait, and even more which would all be considered core vocabulary. Once programmed, the object of the programming follows the commands as coded by the user. The AAC user could do the coding on a device separate from the one they use for communication or work with communication partners to build the code in a paired or group setting. Students who do not use AAC can build programs to reinforce vocabulary for their peers who do.

For example, a group of 7th graders might be invited to work on the following problem: How can we teach other students what the words “in” and “on” mean? The 7th graders might go to Scratch, or any other programming site, and create a program that, when activated, has a character going in and out of objects shouting “In!” and “Out!” each time the character moves.

This game to teach the word “go” was created by two rising 8th graders over summer break. Click the screen shot above to play “Go!” yourself.

When learners are building the code or interacting with whatever the code does, vocabulary is being practiced. In this way, the user can directly learn what each term means by seeing how the object reacts. The objects themselves provide endless opportunities to learn and experience fringe vocabulary as well.

Robots!

Some applications allow users to write code to command actual, tangible devices more commonly known as robots! Examples include the Dot and Dash from Wonder Workshop, Hummingbird and Finch from Bird Brain Technologies, and Evo and Bit from Ozobot.com. Inviting students to program a robot and then watch it follow the commands can be an empowering experience. Not only does it teach coding, but is helps students understand that the language used directly impacts the physical world around them. Plus, robots are just cool! Who wouldn’t want to learn by playing with a robot?

Aided Language Input During and After Coding

Beyond learning the meaning of a specific vocabulary term, the experience of creating and interacting with the execution of the program provides an opportunity for communication partners such as peers, educators, instructional assistants, and family members to model vocabulary on a device using the same language system as the student (i.e., provide aided language input). Just like in any other exchange, communication partners can use the same AAC device as the learner to describe their actions while making the code and while engaging with the resulting action of the code.

Learning to use code in lessons to teach vocabulary to users of AAC devices might seem daunting or complex at first. It is neither! Contemporary tools have made the barrier to entry nearly non-existent. Coding is no longer something reserved for those with doctorates in computer science. Learning to code is now something available to the masses, including (and perhaps especially for) those learning language using an AAC device. Given an opportunity, students and educators alike will find coding to be a fun, practical, engaging, and empowering experience for all involved.

Share your creations, experiences, tools, and programs that you are using with coding to teach language to users of AAC devices on the social media platform of your choice with the hashtag #CoreCoding.

Additional Resources –

—-

Christopher R. Bugaj, MA CCC‐SLP is a founding member the Assistive Technology Team for Loudoun County Public Schools. Chris hosts The A.T.TIPSCAST (http://attipscast.com); a multi‐award winning podcast featuring strategies to design educational experiences and co-hosts the Talking With Tech (http://www.talkingwithtech.net/) podcast featuring interviews and conversations about augmentative and alternative communication. Chris is the co‐author of The Practical (and Fun) Guide to Assistive Technology in Public Schools (http://bit.ly/chewatamazon) published by the International Society on Technology in Education (ISTE) and has designed and instructed online courses for ISTE on the topics of Assistive Technology and Universal Design for Learning. Chris is also the author of ATEval2Go (http://bit.ly/ateval2go), an app for iPad that helps professionals in education perform technology assessments for students. Chris co-authored two chapters for a book published by Brookes Publishing titled Technology Tools for Students with Autism. Chris has presented over 250 live or digital sessions at local, regional, state, national and international events, including TEDx, all of which are listed at http://bit.ly/bugajpresentations. His latest book The New Assistive Tech: Make Learning Awesome For All (http://bit.ly/thenewat4all), also published by ISTE, was published in May of 2018.

Speaker Disclosures – Chris won a free Dash robot and training course from a raffle at the ISTE 2018 conference. The Dash robot is featured in videos mentioned to this article. Chris receives no revenue from any company mentioned in this article. Chris has no non-financial disclosures.

—–

Jill E Senner, PhD, CCC-SLP

SpeakUP

Editor-in-Chief