USSAAC’s SpeakUp editorial committee is excited to introduce a new series honoring USSAAC legends! We hope to launch a quarterly post featuring an interview with one legend from USSAAC. Today, we kick off this series with an interview featuring Sarah Blackstone and Sheela Stuart. We asked them to share their memories on founding the United States Society on Augmentative and Alternative Communication.

Interviews with Sarah Blackstone & Sheela Stuart

Transcript edited by Deirdre Galvin-McLaughlin and Amy Goldman

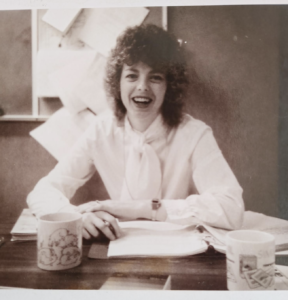

Sarah Blackstone (left) and Sheela Stuart (right)

Interviewer:

So, whose idea was it to establish a US Chapter of ISAAC? Who, why, and when?

Sheela:

At the time, I was associated with Bliss Symbols in Toronto. Howard Shane and I were charged with developing training sessions across the United States for augmentative communication. We were part of ISAAC in those days. It was a very challenging thing to do because of the time differences and lack of money to support the development of these programs. Howard and I were doing our own jobs and then trying to figure this out on the side. It became especially complicated when the treasurer for ISAAC lived in some place in England. So we decided, let’s have our own chapter of ISAAC. So, that’s how I got involved.

Photograph of Sheela Stuart at the time of the founding of USSAAC

Sarah:

I had been working since 1975 in Pittsburgh, PA. and most of my caseload were kids that weren’t able to use their natural speech, which had not even been mentioned to me in graduate school. So, I was feeling “challenged”. I remember dreams I had, trying to figure out a way that I might be able to help these children. We started working in “augmentative communication” long before it was called AAC. It was also a time when some of our AAC companies were starting up. That’s how I met Barry Romich early on and Larry Weiss. Professionals were also going to conferences and meeting each other. And then, ISAAC was formed.

There were a bunch of us that were aware that other ISAAC chapters were being formed in Europe, and we thought, “Why wouldn’t the United States be a chapter?” I mean that’s like a “duh” question, right? Most of the manufacturers were in the United States. People who had money lived in the United States. We had a university system in the United States. How aren’t we an ISAAC chapter?

It was a need. It was a response to a need. It was a growing awareness and ability to actually do something and make a difference. And then it was like, “well, we should”. We should have an organization. We met in Lincoln, Nebraska to get started.

Sheela:

To me, it’s almost cosmic that those of us who got involved were also representative of different perspectives that this organization would have so that when we came together for 2 or 3 of these… what I refer to as torturous meetings… because they were difficult!… and discussed “okay, if we did this, what would it look like?”. It was always valuable that each of us were sort of headlining a point of view.

Dave Beukelman really had this genius. The thing that I remember is, we sat in this conference room in the basement of some place in Nebraska, and we wrote out this charter. In my opinion, Beukelman was the brains behind all that. He knew how to phrase it. He never brought up a single point that wasn’t valid.

USSAAC was certified and incorporated in South Dakota, April 11, 1989.

Sarah:

Dave Beukelman was selected as the past president because he didn’t want to do anything after drafting the charter was over. Dave Yoder was not present at the meeting, so he was selected as the President. And then there was a quick pivot to annoint the President-elect, Judy Montgomery, to take on the presidency because we knew she would get all the things that needed to attended to quickly, done.

Interviewer:

Take us back. Give us an idea of what the context was. What was the “scene” like at the time in terms of resources for AAC, for people who use or needed AAC, or for practitioners in AAC?

Sarah:

There was one thing that we were all concerned about. We didn’t want to be perceived as trying to lord over the AAC work in the United States or to take control. The United States is a big country with 50 states. We were thinking about state chapters at that time.

Sheela:

It also was somewhat threatening to ISAAC, because, even though there were little chapters in Europe and Canada, they were controlled a lot through the Bliss organization. When you do these kinds of things, you need to know inside yourself what the serving philosophy is that’s guiding you, because you’ll be wounded along the way. People will accuse you of intentions that never crossed your mind. People didn’t know how it was going to play out. You had the commercial folk who had an investment. You had the clinical folk who had an investment. You had the educators with ASHA who had an investment. You had folks who were politically interested in being prominent. It required a tremendous amount of tip toeing, and then striding.

The commercial manufacturers were also a huge part of this in as much as they were part and parcel of what’s going to bring this whole service for these folks forward to where it needs to be. Of course, they were competing with one another. At each juncture, it would have been possible that one of these particular elements was really driving the whole thing, and that couldn’t be. It had to be input from each area.

When I look back on it, the thing that I love about it, is there never was any question, among any of us, no matter what our perspective was, why we were doing it. It was so that this underrepresented population would begin to have services and be protected. All of us had experienced that when we would try to provide services for these folks agencies would say “No, they’re not functioning at a level that justify serving them”.

Sarah:

Yes. We were all trying to implement the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142), or the EHA, which guaranteed a free, appropriate public education, or FAPE, to each child with a disability in every state and locality across the country.

Sheela:

One of the things that I felt was a tremendous step forward in service provision and I think USSAAC and the people it involved basically created the steps forward, was when they finally decided that ‘yes, these people could get services.”

And believe it or not. I always thought of ourselves as linking arms and walking forward, saying, ‘No, you cannot do this to this individual.’ You have to let us do what we can do and pay us for it.

I remember when Dave Beukelman said “We have to take it to a policy level, Sheela”. That was so important.

Sarah:

I think it’s important to remember Lew Golinker and Carol Cohen’s role in this too because right from the beginning Lew was engaged in the legal fight. And, he’s still working on this almost every day.

Interviewer:

Just thinking about the original vision for USSAAC, are we there yet? Where are we going? What’s the niche that USSAAC serves that isn’t possible through ASHA SIG 12 or like organizations.

Sarah:

I think this is not about speech-language pathologists, and we’d better not make it about speech language pathologists. This is about people who are denied the right to communication access.

The other thing it’s about is interprofessional collaborative teams. I think one of the things that’s really important is the whole issue of getting away from practicing in silos. If you’re going to make a difference for these individuals, as a speech-language pathologist, you can’t do this by yourself. You almost always need a team. In some facilities and settings it’s easier to build a team than in others. I think it continues to be a challenge in school settings.

Finally, as Sheela said, it’s about creating and implementing policies that makes it against the law to not do the right thing.

Sheela:

USSAAC is charged as the guardian of that principle. We’ve got to always have an organization that will fight for these people’s rights

Sarah

And to be part of a bigger, international vision and mission to do whatever we can to provide communication access for all.